- Home

- Resource

- Explore & Learn

- When Speed Trumps Certainty: How Ebola Changed the Rules of Diagnostic Testing

- Home

- IVD

- By Technology Types

- By Diseases Types

- By Product Types

- Research

- Resource

- Distributors

- Company

In 2014, as Ebola spread through West Africa, health workers faced a harrowing dilemma: wait weeks for accurate test results while patients died or spread the virus, or use unproven rapid tests that might give false results. This crisis forced the World Health Organization (WHO) to rewrite the rulebook for medical innovation, creating a controversial "emergency pass" for diagnostic tools. What unfolded in Sierra Leone and beyond offers critical lessons for how the world responds to future pandemics.

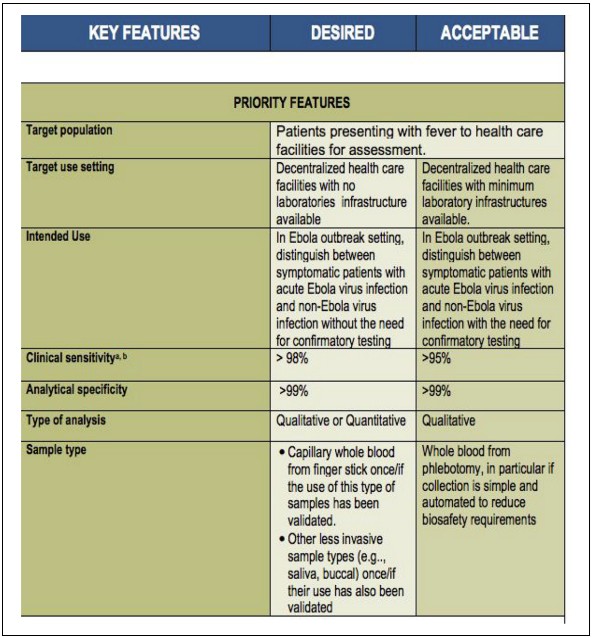

Fig.1 Target product profile for Zaı¨re ebolavirus rapid, simple test to be used in the control of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa (WHO 2014b). (Street A., et al., 2024)

Fig.1 Target product profile for Zaı¨re ebolavirus rapid, simple test to be used in the control of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa (WHO 2014b). (Street A., et al., 2024)

When the WHO declared the 2014-2016 West African Ebola outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, the world was unprepared. Sierra Leone, one of the hardest-hit countries, had a shattered healthcare system—decades of underinvestment had left it with virtually no diagnostic infrastructure. International teams rushed in, setting up makeshift labs in repurposed classrooms where schoolbooks still lined the shelves behind biohazard equipment.

The existing diagnostic tools were woefully inadequate. The standard test, called RT-PCR, required complex equipment, trained technicians, and cold storage—luxuries in rural Sierra Leone. Samples often traveled hundreds of kilometers over bad roads, taking days to reach labs. By the time results arrived, patients had either died or unknowingly infected others. "Diagnostics had been lost in the scramble for Ebola control," the WHO later admitted.

This failure had devastating consequences. In the early weeks, without timely diagnosis, containment efforts collapsed. Funeral rites, crucial to local culture, became super-spreader events because families couldn't safely bury loved ones without confirmation of Ebola. Public trust evaporated as health workers in protective gear seemed more like threats than helpers.

In July 2015, the WHO launched a radical experiment: the Emergency Use Assessment and Listing (EUAL) procedure. Unlike traditional approval processes that demand years of data, EUAL allowed medical products onto the market with "minimal information"—a calculated gamble that some uncertainty was better than no tools at all.

"During a public health emergency, communities may tolerate less certainty about performance and safety," the WHO explained. The goal wasn't to guarantee a product worked perfectly, but to find "thresholds of tolerability" for promising tools in a crisis.

This was regulatory limbo—a temporary space between approval and rejection where manufacturers, scientists, and health workers could figure out what worked in practice. As one WHO official put it, "We weren't looking for perfect tests. We needed tests that could save lives now."

To guide developers, the WHO released a "Target Product Profile" (TPP) outlining ideal vs. acceptable features for Ebola tests:

| Key Feature | Desired | Acceptable |

| Target Setting | Rural facilities with no labs | Rural facilities with basic labs |

| Intended Use | Standalone diagnosis | Needs confirmation |

| Clinical Sensitivity | >98% | 95% |

| Sample Type | Finger-prick blood, saliva | Venous blood |

This document walked a tightrope—ambitious enough to push innovation, flexible enough to accommodate real-world constraints. It wasn't legally binding, but became a reference point for companies racing to develop tests. Two technologies emerged as front-runners: automated RT-PCR machines (highly accurate but bulky) and lateral flow assays (simple, portable "rapid tests" with lower accuracy).

The first test to go through EUAL was the Corgenix ReEBOV Antigen Rapid Test Kit—a simple strip that could return results in 15 minutes. Developed with researchers in Sierra Leone, it seemed like a game-changer for remote communities. But its journey revealed the messy realities of emergency regulation.

When WHO teams arrived in Sierra Leone to evaluate the test, they found improvised labs in repurposed schools. "We had to design protocols on the fly," one researcher recalled. "These weren't controlled lab conditions—they were war zones for public health."

Blood samples, critical for validation, were scarce, and ownership was disputed. International labs hoarded samples, fearing they'd run out. When samples were shared, they came with unknown storage histories, making consistent results impossible. "We ended up pooling samples with similar PCR results because there wasn't enough volume," another scientist explained.

The test's performance varied wildly depending on which "gold standard" it was compared against. Against one reference test, it showed 93% sensitivity; against another, only 85%. A third study claimed 100% sensitivity, but the WHO questioned the methodology.

Despite these inconsistencies, the WHO listed Corgenix in February 2015, not because it was perfect, but because rural clinics had no better options. "In a crisis, 'good enough' can be lifesaving," noted a WHO report.

As the epidemic evolved, so did debates about the Corgenix test. In Kono District, Sierra Leone, health workers praised it as a triage tool. "It helped us separate probable cases quickly, protecting our team," one manager said. But when officials in Freetown heard about its use, they banned it, following WHO guidance that warned of false positives undermining trust.

This tension exposed a fundamental rift: international experts focused on epidemiological accuracy, while frontline workers prioritized immediate utility. "WHO didn't want false positives causing chaos," explained a researcher. "But clinical units still had to transport samples and wait days for results. That never got resolved."

By mid-2015, with case numbers dropping, the calculus shifted. Lower disease prevalence meant rapid tests would produce more false positives. The WHO reversed course, advising against rapid tests in most settings. Meanwhile, automated RT-PCR machines were becoming more widely available, offering greater accuracy as the crisis stabilized.

The EUAL's ambiguous status—endorsement, not authorization—highlighted deeper issues in global health governance. While the WHO claimed no legal authority, the EUAL listing became a de facto requirement for UN procurement. National regulators in Sierra Leone felt sidelined.

"We received no extra resources but faced intense pressure to approve EUAL-listed tests," complained one Sierra Leonean official. International labs often bypassed local regulations entirely, with some accused of smuggling blood samples out of the country for research. "It felt like our sovereignty was being violated in the name of urgency," the official added.

This dynamic wasn't new. As one analysis noted, "Global health emergencies often prioritize speed over local capacity, treating affected countries as testing grounds rather than partners."

By the outbreak's end, the EUAL had mixed results. RT-PCR machines proved invaluable, and some were repurposed for other diseases, though maintenance and supply chain issues limited their long-term impact. Rapid tests, however, largely disappeared—no consensus on their use case left manufacturers with no market.

But the real legacy lies in how the EUAL redefined regulatory possibility. In 2017, it was renamed Emergency Use Listing (EUL) to clarify its relationship with national regulators. Reforms emphasized local involvement in ethical reviews and sample sharing. Most importantly, it established a precedent: in emergencies, regulation could be flexible, adaptive, and inclusive.

The COVID-19 pandemic would later test these lessons, with EUL playing a key role in accelerating vaccine access. But challenges remain. As the authors note, "A truly equitable system would start by asking: whose needs are we prioritizing? What counts as 'tolerable' for whom?"

The Ebola crisis showed that perfect diagnostics are useless if they arrive too late. The EUAL's "liminal space"—between strict regulation and unregulated chaos—proved surprisingly fertile ground for innovation. It demonstrated that uncertainty isn't a failure of regulation but an opportunity for collaboration.

As we face future pandemics, the key will be maintaining this flexibility while centering local voices. "Emergency regulation shouldn't be about lowering standards," the researchers conclude, "but about expanding who gets to define those standards in the first place."

In the end, Ebola taught us that when lives hang in the balance, the best regulations aren't rigid rules—they're frameworks that can adapt, learn, and prioritize people over paperwork.

If you have related needs, please feel free to contact us for more information or product support.

Reference

This article is for research use only. Do not use in any diagnostic or therapeutic application.

Cat.No. GP-DQL-00203

Rotavirus Antigen Group A and Adenovirus Antigen Rapid Test Kit (Colloidal Gold)

Cat.No. GP-DQL-00206

Adenovirus Antigen Rapid Test Kit (Colloidal Gold), Card Style

Cat.No. GP-DQL-00207

Adenovirus Antigen Rapid Test Kit (Colloidal Gold), Strip Style

Cat.No. GP-DQL-00211

Rotavirus Antigen Group A Rapid Test Kit (Colloidal Gold), Card Type

Cat.No. GP-DQL-00212

Rotavirus Antigen Group A Rapid Test Kit (Colloidal Gold), Card Type

Cat.No. IP-00189

Influenza A Rapid Assay Kit

Cat.No. GH-DQL-00200

Follicle-stimulating Hormone Rapid Test Kit (Colloidal Gold)

Cat.No. GH-DQL-00201

Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 1 Rapid Test Kit (Colloidal Gold)

Cat.No. GH-DQL-00202

Luteinizing Hormone Rapid Test Kit (Colloidal Gold)

Cat.No. GH-DQL-00208

Follicle-stimulating Hormone Rapid Test Kit (Colloidal Gold), Strip Style

Cat.No. GH-DQL-00209

Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 1 Rapid Test Kit(Colloidal Gold), Strip Style

Cat.No. GH-DQL-00210

Luteinizing Hormone Rapid Test Kit (Colloidal Gold), Strip Style

Cat.No. IH-HYW-0001

hCG Pregnancy Test Strip

Cat.No. IH-HYW-0002

hCG Pregnancy Test Cassette

Cat.No. IH-HYW-0003

hCG Pregnancy Test Midstream

Cat.No. GD-QCY-0001

Cocaine (COC) Rapid Test Kit

Cat.No. GD-QCY-0002

Marijuana (THC) Rapid Test Kit

Cat.No. GD-QCY-0003

Morphine (MOP300) Rapid Test Kit

Cat.No. GD-QCY-0004

Methamphetamine (MET) Rapid Test Kit

Cat.No. GD-QCY-0005

Methylenedioxymethamphetamine ecstasy (MDMA) Rapid Test Kit

Cat.No. GD-QCY-0006

Amphetamine (AMP) Rapid Test Kit

Cat.No. GD-QCY-0007

Barbiturates (BAR) Rapid Test Kit

Cat.No. GD-QCY-0008

Benzodiazepines (BZO) Rapid Test Kit

Cat.No. GD-QCY-0009

Methadone (MTD) Rapid Test Kit

Cat.No. GD-QCY-0011

Opiate (OPI) Rapid Test Kit

Cat.No. ID-HYW-0002

Multi-Drug Test L-Cup, (5-16 Para)

Cat.No. ID-HYW-0005

Multi-Drug Rapid Test (Dipcard & Cup) with Fentanyl

Cat.No. ID-HYW-0006

Multi-Drug Rapid Test (Dipcard & Cup) without Fentanyl

Cat.No. ID-HYW-0007

Multi-Drug 2~14 Drugs Rapid Test (Dipstick & Dipcard & Cup)

Cat.No. ID-HYW-0008

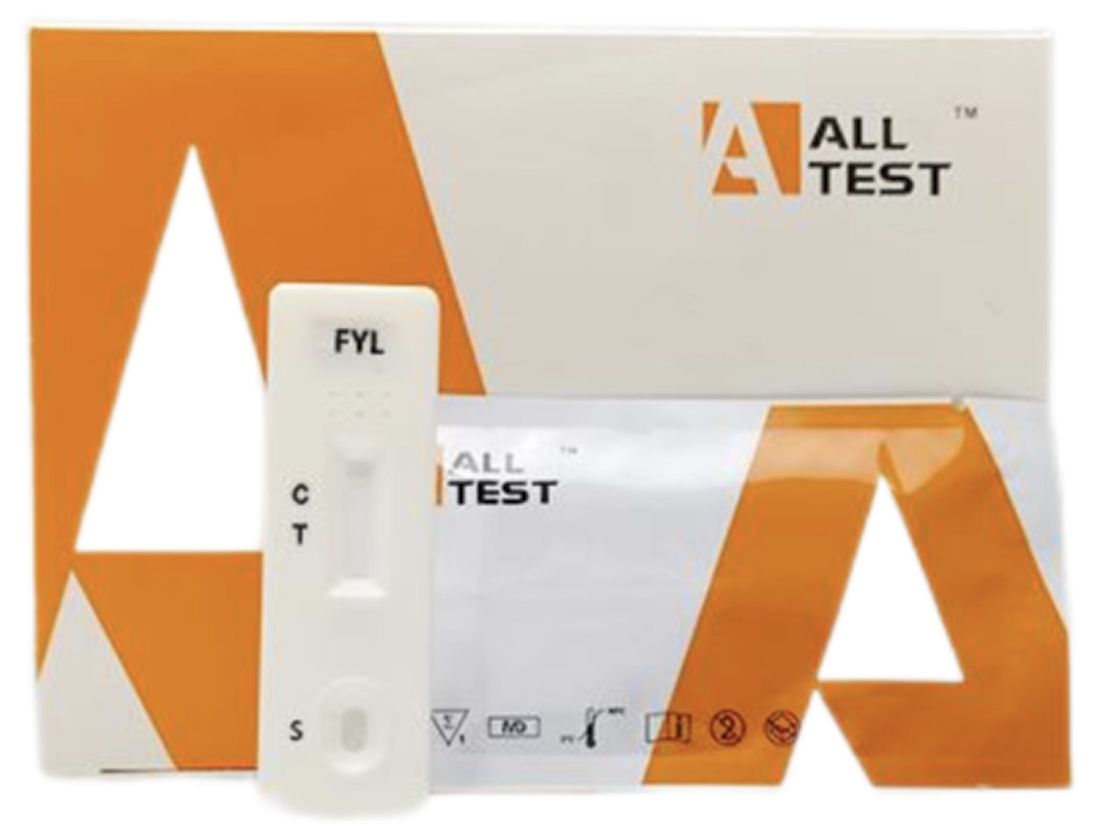

Fentanyl (FYL) Rapid Test (For Prescription Use)

Cat.No. ID-HYW-0009

Fentanyl Urine Test Cassette (CLIA Waived)

Cat.No. ID-HYW-0010

Fentanyl Urine Test Cassette (Home Use)

|

There is no product in your cart. |