- Home

- Resource

- Explore & Learn

- Unveiling the Secrets of SARS-CoV-2: A Deep Dive into Deep Mutational Scanning

- Home

- IVD

- By Technology Types

- By Diseases Types

- By Product Types

- Research

- Resource

- Distributors

- Company

The COVID-19 pandemic, triggered by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, has posed unparalleled challenges to global public health systems. Millions of lives have been directly impacted, while economies worldwide have faced significant disruptions. In the face of such a crisis, the urgent need for effective diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines quickly became evident. At the heart of these efforts was the necessity to deeply understand the virus's biology, especially its proteins, which are crucial for infection, replication, and immune evasion. These proteins not only facilitate the virus's entry into host cells but also enable it to evade the host's immune system, making the development of countermeasures particularly complex. As a result, researchers and scientists have been working tirelessly to decode the virus's genetic makeup, identify potential targets for intervention, and develop innovative strategies to combat its spread and mitigate its impact on human health.

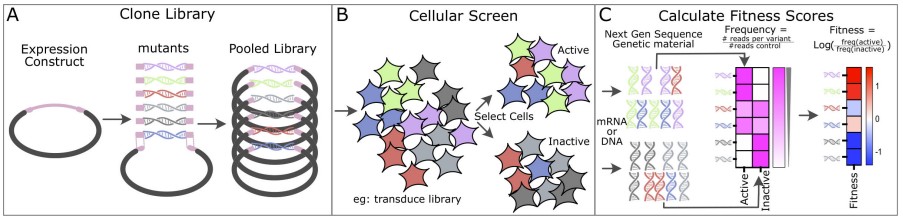

Fig.1 Overview of deep mutational scanning workflow. (Call M. J., et al., 2025)

Fig.1 Overview of deep mutational scanning workflow. (Call M. J., et al., 2025)

The first step in DMS is the generation of a pooled library of protein variants. This is typically achieved using degenerate primers or DNA fragments containing random codons. These tools introduce a diverse array of mutations across the entire protein-coding sequence, creating a library that encompasses thousands to millions of unique protein variants. The goal is to create a comprehensive representation of all possible amino acid substitutions at each position in the protein.

The library is then cloned into an appropriate expression vector, ensuring that each variant can be expressed in a cellular system. This step requires careful design to ensure high fidelity and diversity in the mutational spectrum.

The variant library is introduced into cells, which can be either eukaryotic (such as yeast or mammalian cells) or prokaryotic (such as bacteria). The method of introduction can vary, including viral transduction, transformation, or transfection, depending on the host system and the specific requirements of the experiment.

Once inside the cells, the protein variants are expressed, allowing the functional consequences of each mutation to be assessed in a biological context. This step is critical because it enables the evaluation of protein function within the complex environment of a living cell, where interactions with other cellular components and regulatory mechanisms can influence the outcome.

After expression, the cells are subjected to functional assays designed to measure specific protein functions. These assays can vary widely depending on the protein of interest and the research question being addressed. Common assays include:

Enzymatic Activity Assays: Measuring the catalytic efficiency or substrate specificity of enzyme variants.

Binding Affinity Assays: Evaluating the ability of protein variants to bind specific ligands, substrates, or other proteins.

Cell Growth Assays: Assessing the impact of mutations on cell viability, proliferation, or other growth-related phenotypes.

The choice of assay is crucial, as it determines the functional readout and the type of data generated. The assays must be carefully optimized to ensure that they accurately reflect the functional consequences of the mutations.

Following the functional assays, DNA or mRNA is recovered from selected populations of cells. This genetic material is then prepared for next-generation sequencing (NGS). The sequencing process generates a large dataset of reads, which are aligned to the reference protein sequence to identify the specific mutations present in each variant.

The read counts for each variant are converted into frequencies, reflecting the relative abundance of each mutant in the population. A log ratio is then calculated to define a fitness score for each variant. This score quantifies the impact of each mutation on protein function, with higher scores indicating better function and lower scores indicating reduced or lost function.

Advanced computational tools and statistical methods are used to analyze the data, identify significant mutational effects, and generate functional maps of the protein. These maps provide a visual representation of the functional landscape, highlighting critical residues, functional domains, and regions of the protein that are more tolerant to mutations.

If you have related needs, please feel free to contact us for more information or product support.

Reference

This article is for research use only. Do not use in any diagnostic or therapeutic application.

|

There is no product in your cart. |